Q4 2025

p-less Sampling

A robust LLM decoding strategy that is hyperparameter-free, entropy-aware and information-theoretic.

In this research paper, we introduce a novel approach of sampling named \(\rho\)-less sampling for text generation in autoregressive models. We discuss what such models are and why this sampling technique is valuable for the AI/ML practitioners. We’ll begin by exploring autoregressive models and then provide a comparison of existing sampling techniques — and what \(\rho\)-less sampling offers that’s different.

Autoregressive models

A transformer-based large language model LLM is, at a basic level, a software system that takes in text and generates text in response. Once a large enough model is trained on a large, high quality big data, it should be capable of generating useful outputs. The interesting part is that the model doesn’t generate the entire text in one go; instead, it generates a single token at a time. Each single token generation step is called a forward pass. After each token is generated, the model’s output is appended to its input prompt. The model then generates the next token and it’s presented to the model again for another forward pass. This goes on sequentially. These models are known as autoregressive models.

Decoding strategy and sampling

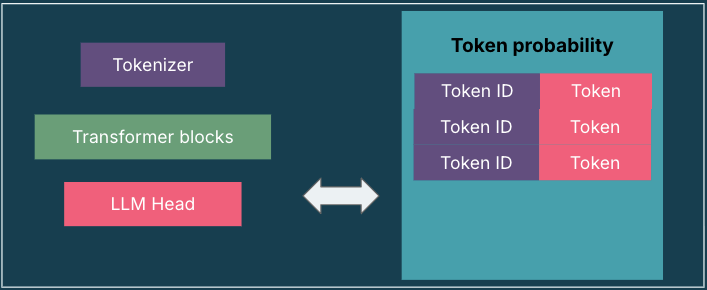

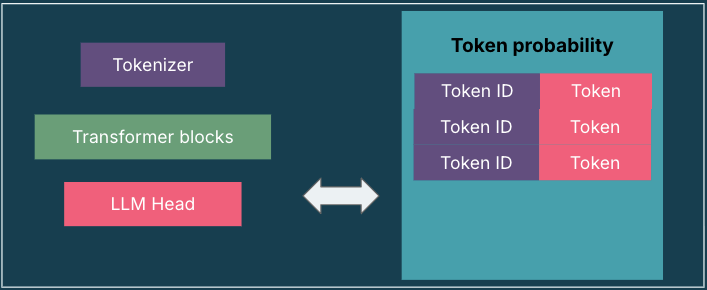

Autoregressive models contain three components: the tokenizer, the stack of transformers and the language model (LM) head. The first and the last components are particularly relevant for our discussion here. The tokenizer breaks the text into a sequence of token-ids that then become the input to the neural network — a stack of transformers that do all the processing. The output layer is LM head; this translates the output of the stack into the probabilities of the token distribution for the next token. The method through which a single token from the probability distribution is chosen is called a decoding strategy. The impressive capabilities of modern LLMs have been aided by advancements in sampling-based decoding strategies. There are a number of approaches but we’ll discuss one in particular in this post - the \(\rho\)-less sampling.

Diagram - 1

The diagram illustrates the overall architecture of the transformer-based LLM and its decoding process. After completing the forward pass, the model outputs a probability distribution over all tokens in the vocabulary. (ref: Jay Alammar et al.)

Comparing existing popular decoding strategies

Before we explore \(\rho\)-less sampling in more detail, let’s first look at a number of other popular decoding strategies. This will help us understand the uniqueness and the advantages of \(\rho\)-less sampling technique.

While decoding the text, the model excludes low probability tokens because they disrupt the coherence of the output. Top-\(\kappa\) sampling limits sampling to the \(\kappa\) most probable tokens. However, this leads to incoherence in the output when the probability distribution is peaked or very uniform. Top-\(\rho\) sampling samples form the highest-probability tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds the threshold -\(\rho\), whereas the -sampling truncates all tokens with probabilities below a cut-off threshold . But both techniques lack the ability to adapt to high entropy conditions where temperature is high. Such conditions occur frequently when output diversity is needed.

Another sampling technique called -sampling defines the threshold as the minimum of and a scaled negative Shannon entropy exponential quantity. But this needs additional hyperparameter tuning; it also assumes a uniform distribution baseline which may differ significantly from the true distribution. This means we need to control randomness in a way that keeps the output text fluent but interesting. The above methods don’t adapt dynamic thresholds to model’s token distribution changes at each step.

That’s where Mirostat and min-\(\rho\) sampling comes in. Mirostat sampling is a feedback-based decoding technique that assumes token probabilities follow Zipf’s Law; it dynamically adjusts its sampling threshold based on an acceptable level of unpredictability and uses a learning rate to control the adjustment speed. Min-\(\rho\) sampling defines the truncation threshold as a fraction of the maximum token probability, introducing a single scaling hyperparameter. This approach improves stability under high-temperature decoding, but remains sensitive to hyperparameter tuning and relies on a single-point statistic of the token probability distribution. This limits its adaptability.

Why do we need a new decoding strategy?

The main idea behind \(\rho\)-less sampling is to make token selection during LLM decoding more deliberate and data-driven, as opposed to arbitrary methods like the ones mentioned earlier. Why not leverage the entire probability distribution? Imagine randomly selecting a token, and it just happens to be the correct one (according to the ground truth). The expected probability of this event sets a natural threshold — what we call \(\rho\)-less. This approach introduces a new, parameter-free decoding strategy for LLMs that’s based on informed decision-making rather than randomness.

The technique is based on how concentrated or spread the probabilities are. We call it the second moment of the probability distribution.

Mathematically, it can be represented like this: it as follows:

|V| = vocabulary size

M[P] = mean of squared probabilities (the second moment)

If the distribution is flat (i.e. there are many similar probabilities), M[P] is small therefore L[P]] is small. This means there’s greater uncertainty, so more tokens are included.

\[L[P] : = \sum_{i=1}^{|v|} (P(x_i)^2\]

\[= |V| \times \left\{ \frac{1}{|V|} \sum_{i=1}^{|V|} \left( P(x_i \right)^2 \right\}\]

L[P] = |V| x M[P]

So, L[P] ∝ M[P]

If the distribution is peaked (ie. a few tokens dominate), M[P] is large therefore L[P] is large. This means the model is more confident, so fewer tokens pass the threshold.

In short, \(\rho\)-less adapts automatically to model output entropy.

The technique dynamically adjusts the truncation threshold at each time-step using the entire token probability distribution. The concept is grounded on solid foundations of information theory. Information theory is a field that studies how to measure and manage uncertainty in probability distributions. Its core idea is that uncertainty can be quantified—and the popular approach is through entropy, which tells us how unpredictable a distribution is (high entropy = more uncertainty, low entropy = more confidence).

The \(\rho\)-less sampling takes advantage of this idea by using the expected probability of correctly guessing the next token — as its truncation threshold. This expectation depends directly on the entropy of the model’s output distribution. So:

When entropy is low (model is confident), the expected correct probability is higher, and \(\rho\)-less sets a higher threshold.

When entropy is high (model is uncertain), the expected correct probability is lower, and \(\rho\)-less sets a lower threshold.

- However, the alternative techniques, who do not use this technique, suffer from text degeneration because they do not consider the entropy of the entire probability distribution while computing the threshold. The technique doesn’t impose parametric assumptions or need hyperparameter tuning, which offers a robust model-agnostic threshold — even including in unpredictable situations.

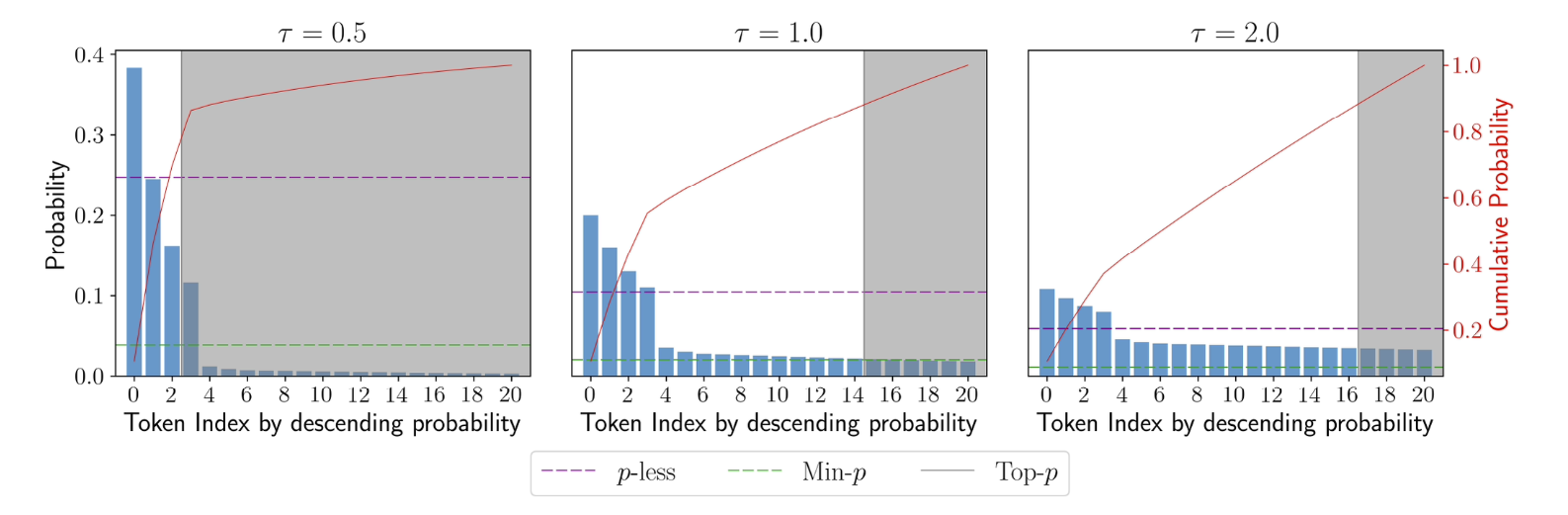

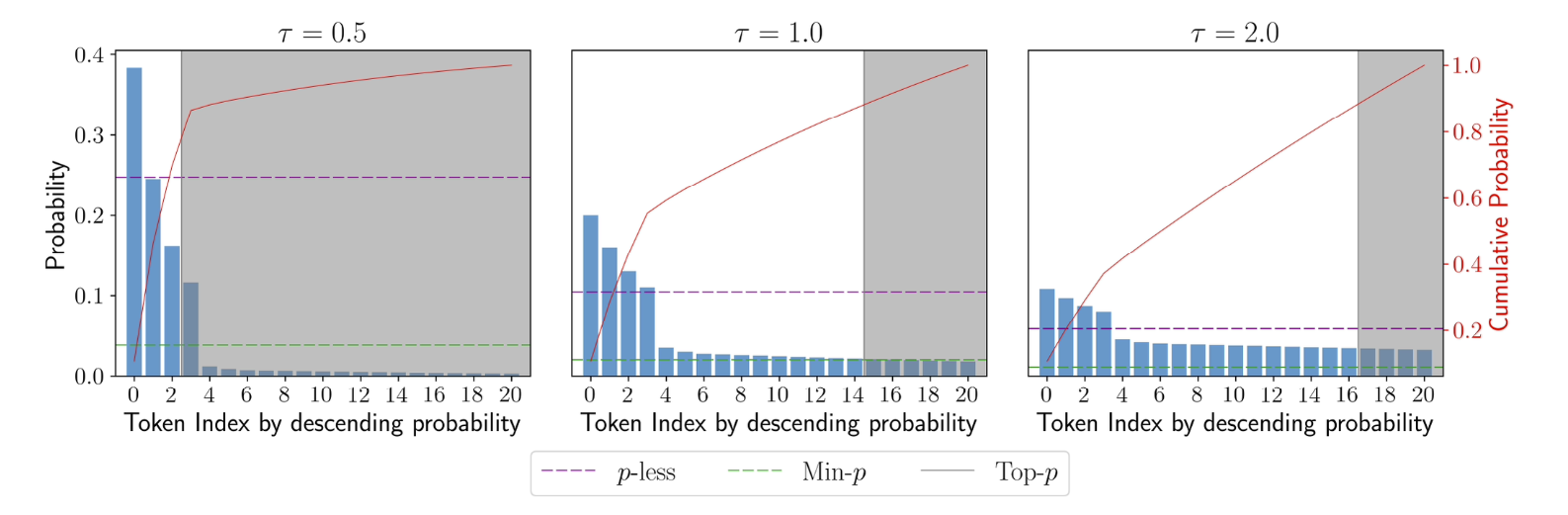

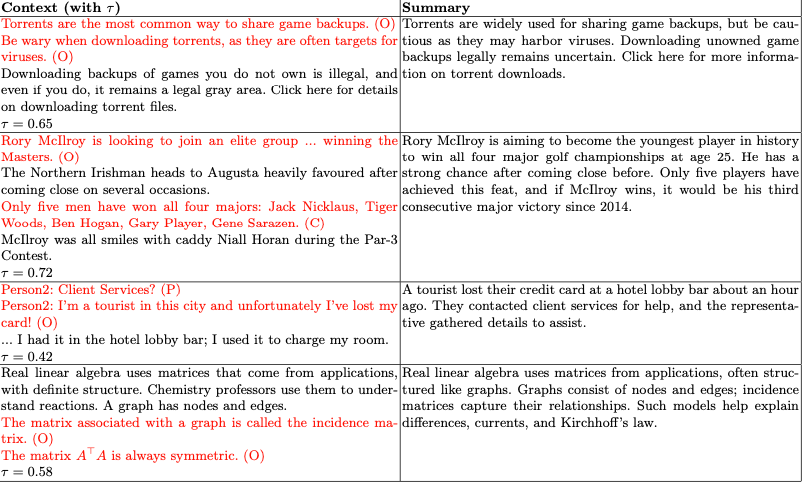

Figure: 1

A comparison of truncation thresholds produced by -less, min-, and top- for token probability distribution with different applied temperatures (). As temperature increases, -less avoids admitting a large number of lower-likelihood tokens by considering the entropy of the distribution in computing the threshold.

\(\rho\) -less is practically effective while strongly interpretable with theory. Specifically, \(\rho\)-less is compatible with interpretations in probability theory, entropies and statistical moments — as opposed to other methods that employ fixed heuristic parameters and don’t leverage full information from the LLM output distribution.

\(\rho\)-less is also valid and bounded. It guarantees a threshold that produces a non-empty token sampling set. This is in contrast to other methods that can meet with edge cases. If you’re interested, take a look at the original work for the detailed proof.

How does \(\rho\)-less sampling work?

Before formally describing the technique, let’s try and understand it in a relatively simple way. The \(\rho\)-less sampling dynamically adapts the token selection threshold at each decoding step by leveraging the entire probability distribution. It computes a “correct random guess” likelihood as a principled cutoff, admitting only tokens above this threshold. The method is entropy-aware, which means the higher uncertainty (entropy) expands the candidate set to include lower-probability tokens, while lower uncertainty narrows the set, ensuring a balance between diversity and coherence in generated text.

Let’s now dive a bit deeper to understand the technique at a mathematical level.

V is the set of all possible tokens (model’s vocabulary)

\(v \in V\) is a single token from the vocabulary

At every decoding step t, the model decides the next token.

S represents the sampled token

T represents the true token (the ground truth)

\(\rho(S = v)\) denote the probability that token \(v\) is sampled.

\(\rho(\tau = v)\) denote the probability that token is the correct token in the “ground truth” sense.

We know that,

\(P_{\theta}(v \mid x_{1:t-1})\)

This is the probability the model (with parameters θ) assigns to token \(v\) given the previous context x₁, x₂ ,…,xₜ₋₁ . All the autoregressive models work on this formula

\(L[P_{\theta}]\) defines the model’s predicted token distribution conditioned on the given token sequence x₁:ₜ₋₁ where θ are the language model parameters. It’s the intersection (choosing the token ) of the two sets: the sampling and true distribution as shown here:

\(L[P_{\theta}] := \sum\limits_{v \in V} \rho(S = v \,\cap\, \tau = v \mid x_{1:t-1})\)

This can be expanded as:

\(\sum\limits_{v \in V} \rho(S = v \mid x_{1:t-1}) \; \rho(\tau = v \mid x_{1:t-1})\)

Sampling (S) and correctness (τ) are independent events (no feedback involved). We have access to the predicted token distribution of the language model and no other external augmentation resources; we’ll therefore take it as our best empirical estimate of the true token distribution, i.e.

\(\rho(\tau = v) = P_{\theta}(v \mid x_{1:t-1})\).

So we have,

\(L[P_{\theta}] = \sum\limits_{v \in V} P_{\theta}(v \mid x_{1:t-1})^{2}\)

This is the foundation step of the ρ-less technique.

The \(\rho\)-less sampling technique in few intuitive steps

Based on the above basics, we can define the process of \(\rho\)-less technique as follows:

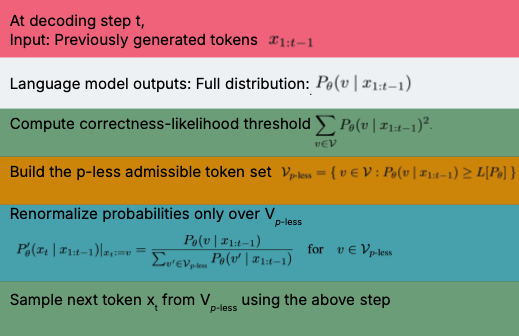

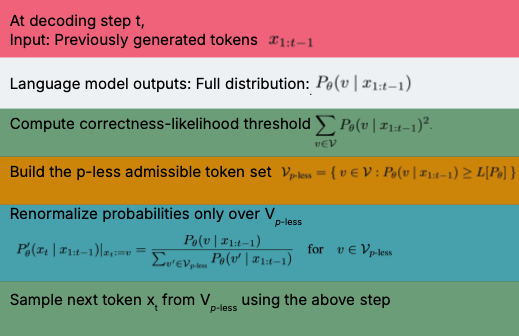

Diagram - 2

The diagram illustrates the process of \(\rho\)-less sampling technique

Here’s the mathematical explanation of all the steps:

Step 1 :

Determine the threshold probability L[Pθ] using the equation below:

\begin{equation} L[P_\theta] = \sum_{v \in V} P_\theta (v \mid x_{1:t-1})^2 \end{equation}

Step 2:

Construct the sampling set with tokens whose probabilities are at least the threshold probability.

The sampling set is \(V_{\rho\text{-less}}\)

\begin{equation} V_{\rho\text{-less}} = \{ v \in V : P_\theta (v \mid x_{1:t-1}) \geq L[P_\theta] \} \end{equation}

Step 3:

Sample from the set in step two the next token xt , according to the normalized token probabilities \(P'_{\theta}\)

probabilities $P'_\theta$: \begin{equation} P'\theta (x_t \mid x_{1:t-1})|_{x_t:=v} = \frac{P\theta (v \mid x_{1:t-1})}{\sum_{v' \in V_{\rho\text{-less}}} P\theta (v' \mid x_{1:t-1})} \end{equation} for \(v \in V_{\rho\text{-less}}\)

The \(\rho\)-less-norm sampling extension

\(\rho\)-less-norm extends \(\rho\)-less by relaxing the sampling threshold. It does this by subtracting the normalized likelihood of an incorrect random guess, allowing the model to admit a broader set of candidate tokens. The result is a decoding behavior that prioritizes diversity over strict coherence, making it well-suited for creative or exploratory generation tasks.

The p-less\(_{\text{norm}}\) is denoted by \(\overline{L}[P_{\theta}]\)

\(\overline{L}[P_{\theta}] := L[P_{\theta}] - \frac{1}{|V|-1} \times \sum_{u, v \in V, u, v \neq 0} P_{\theta} (u \mid x_{1:t-1}) P_{\theta} (v \mid x_{1:t-1})\)

(Probability of a randomly sampled and incorrect token)

\(= \frac{|V|}{|V|-1} \, L[P_{\theta}] - \frac{1}{|V|-1}\)

Here, \(\frac{1}{|V|-1}\) gives the ratio of the possible number of correct to incorrect outcomes.

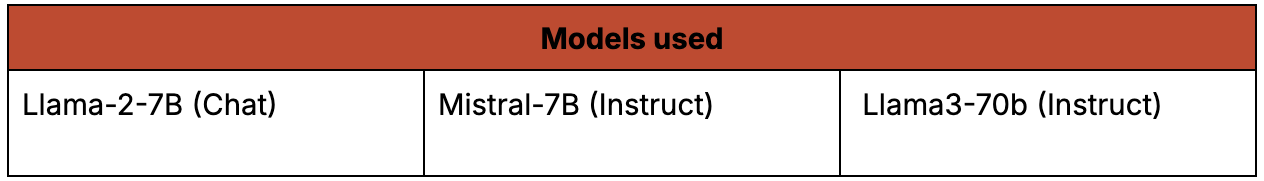

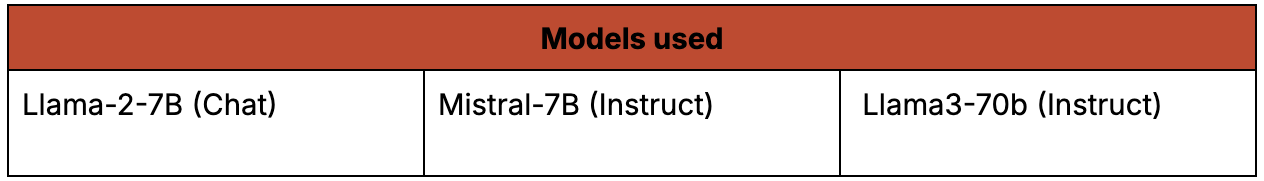

Models and datasets

The \(\rho\)-less sampling technique was performed on the following models to check the consistency of the results as well as the universality of the technique.

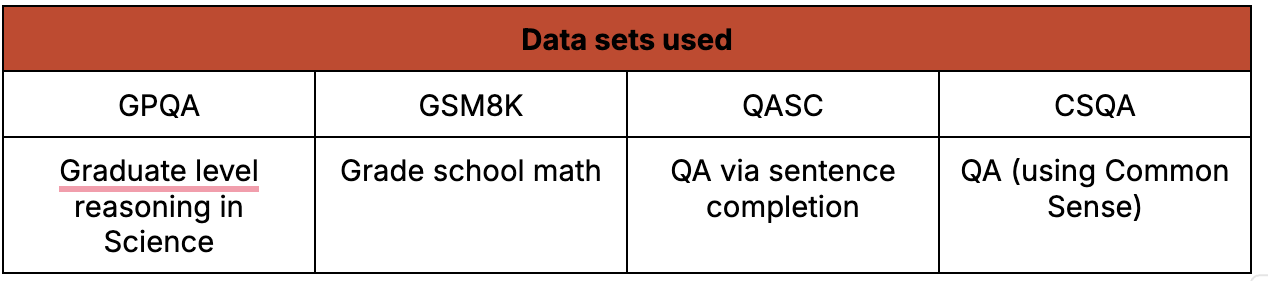

The technique was tested using these datasets:

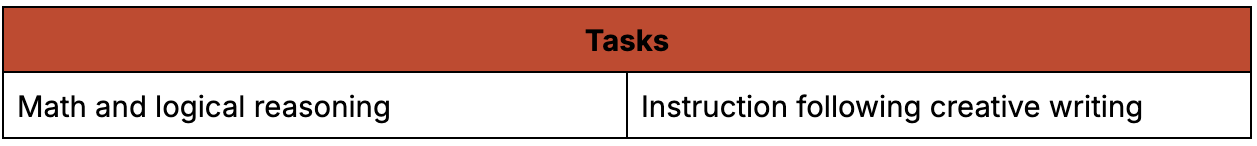

The technique was used to perform the following two tasks using the datasets on the above mentioned models.

We’ll now discuss the results. For a detailed discussion, please refer to the original research paper here.

The \(\rho\)-less sampling technique test results

After testing the \(\rho\)-less sampling technique on three LLMs and five datasets spanning math, logical reasoning and creative writing skills we have proved the following benefits of this new technique:

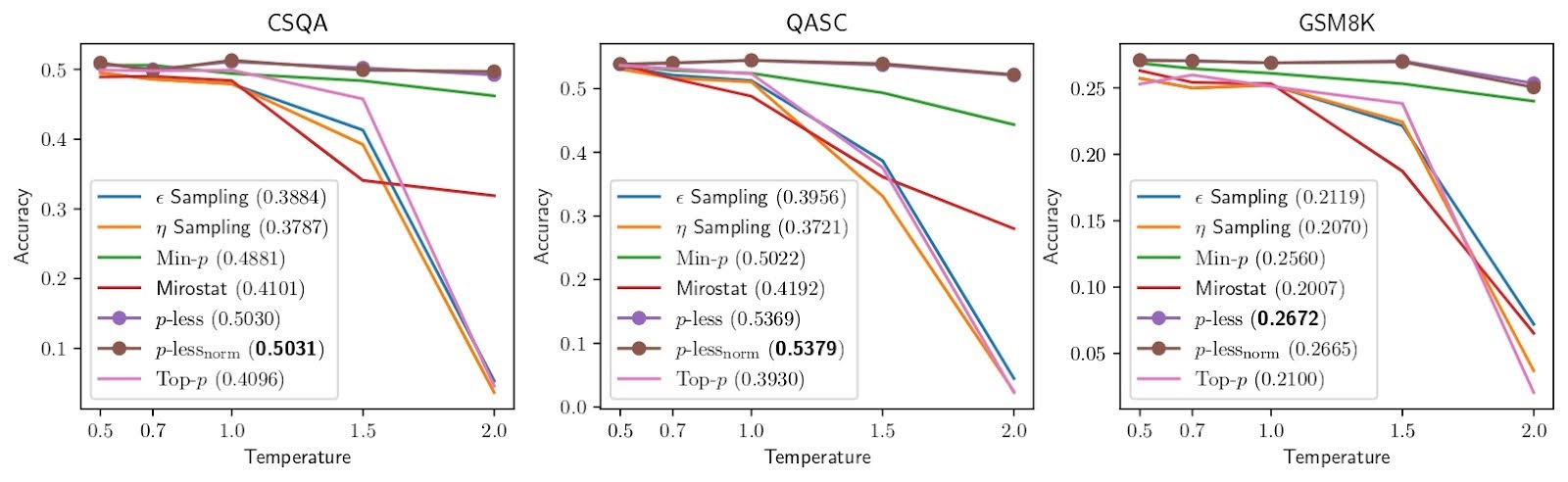

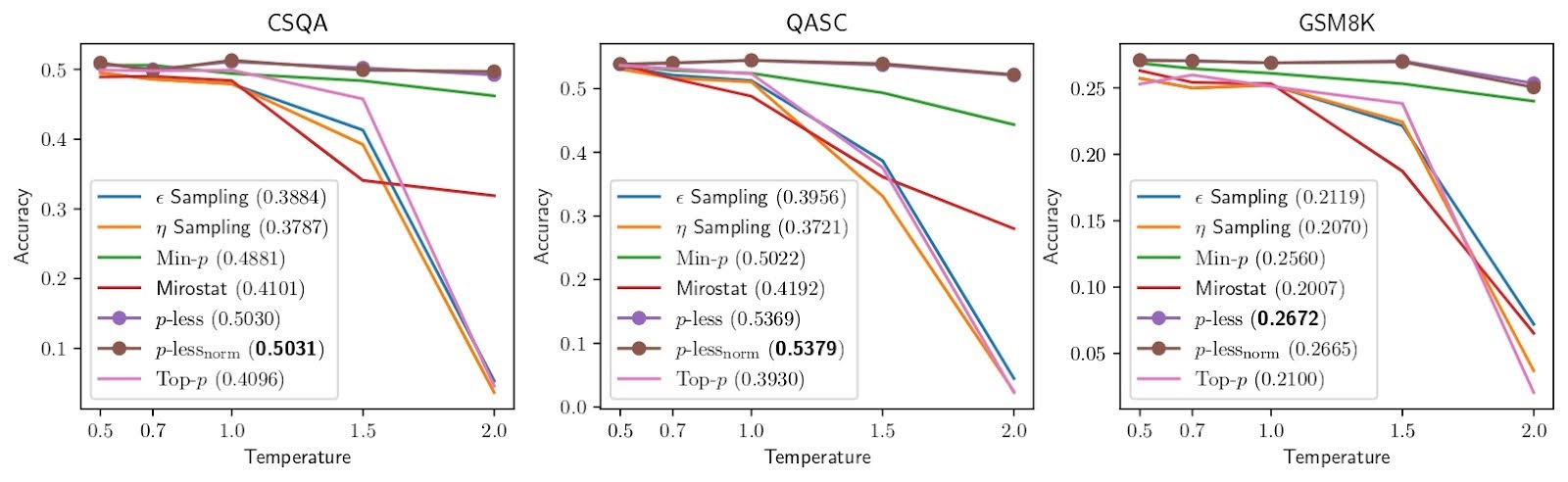

The technique consistently achieves high accuracy across a wide range of temperature values especially in math and logical reasoning tasks (refer Figure - 2)

Figure - 2

Accuracy vs. temperature curves of each method for each of the four math and logical reasoning datasets using Mistral -7b. The legend provides AUC values. (The AUC value is an area under the accuracy - temperature curve for each method (normalized between 0.0 and 1.0).

The technique provides best performance in automated evaluations for the writing prompts dataset. This helps for better performance in creative writing.

The technique demonstrates superior inference-time efficiency over the other methods, by offering:

higher token sampling speed and

generating concise text without sacrificing task-specificity.

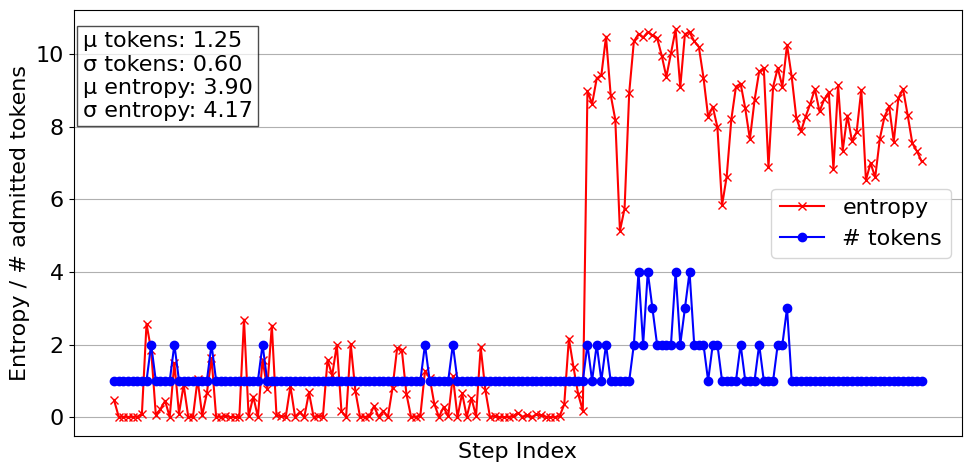

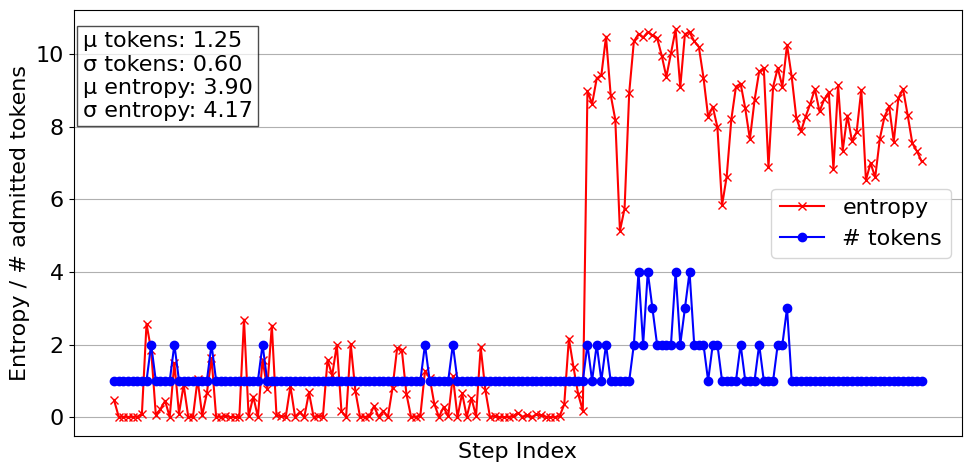

The technique enforces a form of entropy-aware regularization, mitigating token overcommitment in ambiguous regions and preserving semantic fidelity. (Refer to figure 3)

Figure 3

The plot shows step-wise entropy and the number of admitted tokens for a GSM8K question answered with Llama3-70b. Even though entropy is extraordinarily high, the number of admitted tokens remains low. This demonstrates \(\rho\)-less’s selectivity in admitting more tokens and effectiveness in subduing verbosity.

The truncation threshold of \(\rho\)-less sampling dynamically adjusts with temperatures unlike other methods where hyper-parameters aren’t meaningful when the temperatures approach zero or infinity. (refer figure 1)

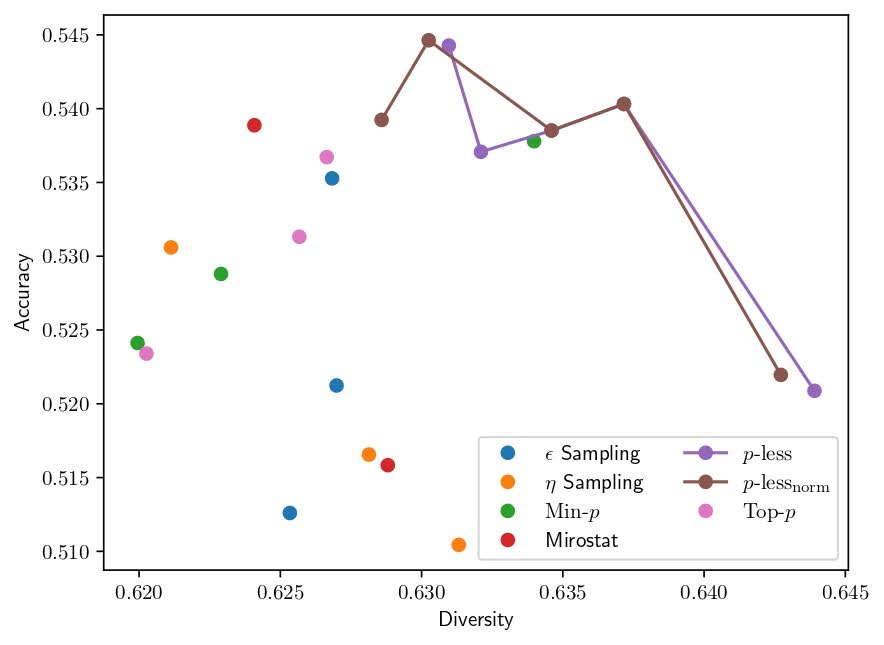

The \(\rho\)-less and \(\rho\)-less norm produce higher accuracy at a given level of generation diversity than other sampling methods, exhibiting a pareto dominance along the diversity-accuracy frontier. (refer Figure - 4)

Figure - 4

QASC accuracy vs. diversity for various techniques

Implementation

Keen to implement a \(\rho\)-less method on your own LLM? Please check the link here. The page contains all the necessary information like installation details with examples along with the code snippets you can apply to your LLM. The original research paper can be found here.

Conclusion

We’ve developed \(\rho\)-less sampling, a new approach to sampling-based decoding that does away with hyperparameter tuning altogether. Instead of forcing practitioners to hunt for the “right” cutoff, \(\rho\)-less brings the best qualities of existing sampling techniques together under one unified method.

Across three LLMs and four very different datasets — from math and logical reasoning to creative writing — \(\rho\)-less delivered consistently strong results, even as temperature settings changed. Other decoding strategies, by contrast, tended to fall off a cliff as temperature increased.

There’s a performance upside too: \(\rho\)-less speeds up inference, with faster token sampling and shorter generations.

The takeaway? When we ground LLM decoding in information theory, we get a method that’s both systematic and highly effective in real-world use.

Steering smarter

Why K-Steering is reshaping LLM activation engineering

By Amirali Abdullah, Parag Mahajani

Background

Activation engineering is a way to directly edit a model’s internal activations to change how it behaves. If the nodes in a neural net are like brain cells, then the activations are analogous to the brain cells’ firing patterns; they shift and change depending on model inputs. What if you could tweak those patterns to change the thoughts that follow?

The simplest form of activation engineering is called linear steering. This is where you find a direction in the activation space that represents a specific trait, like positivity or formality, and add it during inference while the model is running. Turner et al. (2023), for example, showed how you can build a sentiment vector by contrasting prompts like I love this and I hate this, then inject that vector to flip the model’s tone from negative to positive.

This works well for single traits, but it gets messy when you try combining vectors. Adding two vectors, like one for safety and one for formality, often fails to give you safe and formal text. Instead, the traits can cancel each other out, or the model drifts into awkward or stilted language. Features don’t just stack neatly; they collide in unpredictable ways.

To handle this, researchers at Thoughtworks are exploring non-linear steering methods.

These go beyond simple vector addition by modeling how traits overlap and entangle inside the network. The work is still early, but it shows promise for steering multiple traits at once while keeping the text natural and fluent.

Why activation engineering?

In the recent past, language model control has been performed using various approaches. The most popular ones are:

Intervening on weights, with supervised fine-tuning on desired outputs.

Intervening on weights with reinforcement learning using human feedback (RLHF) or with AI feedback.

Intervening at decoding time, using constrained generation.

Intervening on the prompt, as with manual or automated prompt engineering

However, all of these approaches have certain limitations. For example, fine-tuning takes a long time, careful dataset curation and heavy computing resources, which makes it expensive and impractical in many instances. Prompt engineering is unreliable and can elicit a limited range of model capabilities.

Activation engineering is a recent technique gaining popularity for steering a pre-trained large language model (LLM) to a desired behavior. The uniqueness of this approach is that it’s achieved at inference time by strategically perturbing activations at specific intermediate layers of the model. These activations are nothing but multi-dimensional vectors added only to the “forward passes” of the LLM.

Activation engineering provides a more direct and interpretable approach to control the model output. It also lowers the operational cost, saves time and improves the model’s reliability for the desired output.

Various approaches were developed to create vectors of activations, each having its own peculiarities. Here are a few popular ones:

Approach 1:

This approach is called ActAdd, where vectors are added to a subset of sequence positions. These generally require only a handful of examples for validation and can be computed directly from simple token embeddings.

Approach 2:

This approach, called contrastive activation addition (CAA), is a technique to steer language models by changing their internal activations during each forward pass. CAA creates steering vectors by averaging the differences in activations between pairs of examples that show opposite behaviors. These are usually computed with the activations of the last token of the response, but the position used may vary. During inference, these steering vectors are added to the model’s activations at every token position after the user’s prompt, with either a positive or negative weight, allowing fine-grained control over the behavior.

Although popular, both approaches are linear and use an additive function in the activation space. As such, neither solves the challenge of controlling multiple behavioral attributes of the model at inference time. One has to go beyond linear steering.

The K-steering method is one potential approach.

K-Steering: Leveraging gradients of multi-layer perceptron (MLP) classifiers on activations

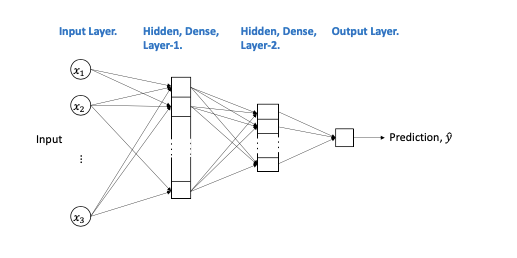

K-Steering is a novel approach designed to overcome the challenges of linear steering to achieve multi-attribute control of large language models. We have used the multi-layer perceptron (MLP) in this work. So before diving deeper into the approach, let’s provide some background on the multi-layer perceptron (MLP), a simple feed-forward neural network that can be used to recognize when certain behaviors appear in the model’s internal representations.

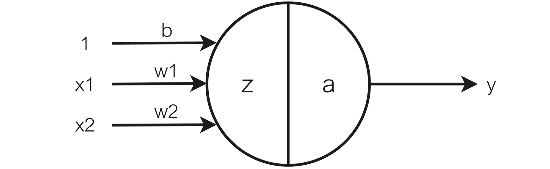

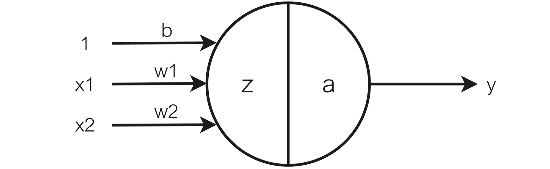

Historically, perceptrons proved to be powerful classifiers. A single perceptron works like a neuron, accepting multiple inputs and giving a binary pulse as a response. An MLP contains many intermediate layers of neurons called nodes. Each node includes a non-linear activation function that’s differentiable. Mathematically, a neuron is a perceptron made of weights and bias parameters. A high-level representation of a multi-layer perceptron is shown here:

Figure 1: MLP architecture

Each node contains two mathematical functions working in a pair. They are called a summation operator ∑ and an activation function σ(x).

The activation function receives the output from the summation operator and transforms it into the final output for a particular node when the input signal exceeds the threshold value. Let us take an example.

The node shown here has two inputs, x1 and x2, providing an output y. Another input 1 to the node is bias b, which is always multiplied by the input 1.

Figure 2: - Activation function

Output

z = w1.x1 + w2.x2 + b

y = a(z)

For a simple linear node,

a(z) = z

y = w1.x1 + w2.x2 + b

The function a(z) is the activation function.

Another important reason to use an activation function is to introduce non-linearity to the neural network. This non-linearity offers the power of breaking down a problem into sub-problems and combining their results to arrive at the overall solution. There are various types of activation functions. The most popular are as follows:

The simplest way to understand an activation function is to imagine a neural network as a collection of functions where the "weights" define the numeric values of the functions. The "activations" are then the output values of these functions on a per input level, and these can be altered without changes to the underlying "weights" of the neural network.

- Anil Ananthaswamy (The author of 'Why machines learn - The elegant maths behind modern AI)

- Sigmoid” activation function a(z) = \(\sigma\)(z), where:

\(\sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}}\)

ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit)

a(z) = \(\sigma\)(z)

z, z >= 0

0, z < 0

GeLU (Gaussian error Linear Unit)

a(z) = \(\sigma\)(z) = x⋅Φ(z)=0.5z(1+tanh(2/π(z+0.044715x3)))

K-Steering trains a single, non-linear multi-label classifier on the model’s hidden activations. At inference time, the method uses the gradients of this classifier to guide the model’s behavior. These gradients indicate the subtle changes needed in the model’s internal activations to steer its output towards or away from desired attributes.

Returning to our analogy of a neural network to a brain, this is like gently nudging the model’s internal thought process towards text with a human desired attribute.

Advantages of K-steering method

The K-steering method has a number of advantages, including:

Simultaneous control. The method gives greater control over the model's behaviors. This removes the need to prepare and compute separate steering interventions for each attribute while offering more robust handling of interactions between different behaviors.

Scalable design. The method scales smoothly to larger sets of attributes without added code complexity.

Balanced steering. The method allows the classifier to balance multiple steering attributes, unlike other methods that simply average multiple steering directions, diluting the aggregate effect.

Fine-grained tuning. Steering results can be enhanced by applying extra gradient steps with smaller sizes, allowing fine-grained control over the behavior.

As a hypothetical example, let us use an MLP with two hidden layers with 256 units each and ReLU activations. The MLP is trained only on the final token’s activation. During steering, the classifier is applied to all token positions in the sequence to influence generation more broadly. Once trained, this MLP acts as a detector: it can spot whether the LLM is about to generate content aligned with a target label (for example, polite or humorous). Then, during inference, the gradient of this classifier with respect to the activation is used to steer the output. Let’s try and understand it mathematically.

Ai′ = ai−α.∇ai.L(gϕ(ai))

where:

ai: The activation vector from the LLM. It is the representation (intermediate outputs) from the model at a specific layer, like a "snapshot" of what the model is thinking at each layer output. It is formulated as ai ∈ ℝ^{d_seq × d_model}, i.e., (sequence length × model dimension)

gϕ: The classifier. A small, separate MLP. It looks at activations from the model and predicts one of K behaviors (like tones or styles). Its job is to tell whether a hidden activation reflects the behavior, like the tone.

gϕ(ai): the classifier’s prediction for that activation.

L: The loss function. It predicts how far the classifier is from predicting the desired behavior.

∇ai.L: The gradient vector of that loss function w.r.t. the activation. It tells us how to change the activation to make the classifier more confident about the target behavior.

α: A scaling factor that controls how strong the steering is.

ai′: The new, edited activation.

fθ: Model parameters θ (its internal learned weights).

K: Number of categories. These are the types of behaviors we want to steer the model towards or away from.

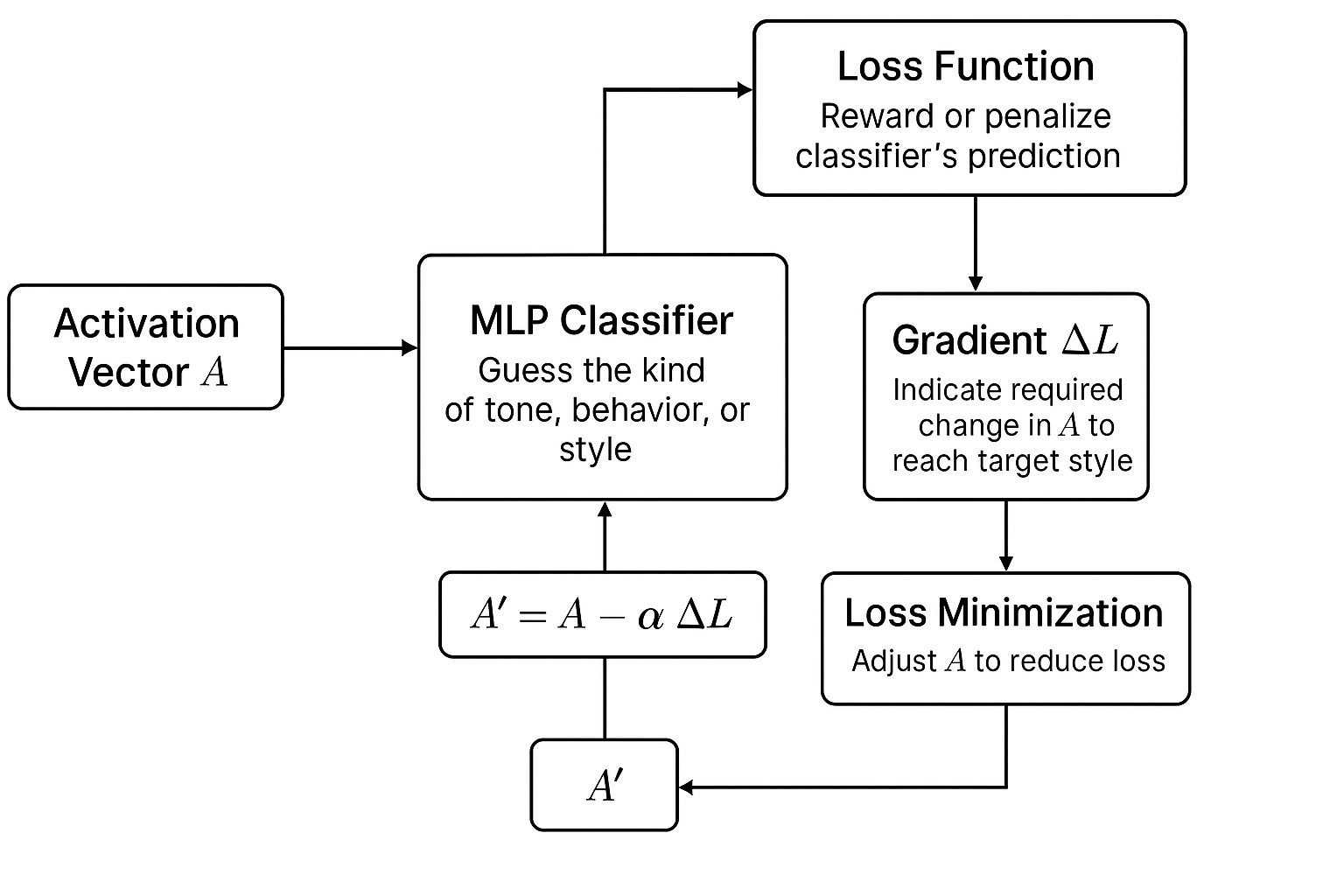

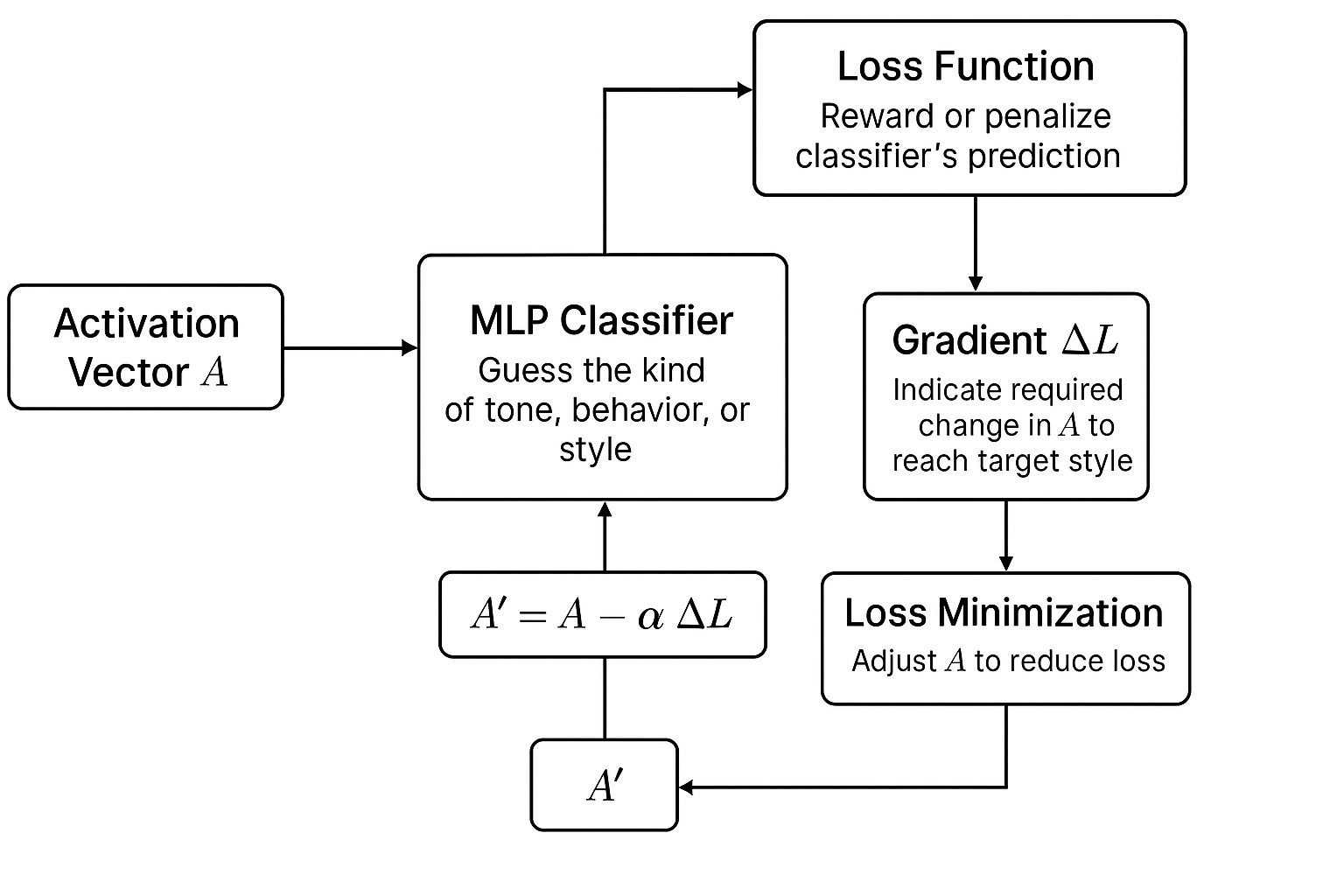

The K-Steering process

The process can be simplified into four stages.

Figure 3: - K-steering process

The MLP classifier looks at the activation vector A to “guess” the kind of tone, behavior and style it reflects (e.g., sarcastic or formal). In a neural network like LLM, every layer takes in numbers, performs mathematical operations, and produces a new set of numbers. This new set is passed on to the next layer. This set is called an activation (or activation vector if it’s one-dimensional). So, A is the output of a specific layer after applying its activation function.

The “loss function”: For an activation vector A, calculate a steering loss that penalizes higher logits from a classifier on A for undesired labels and rewards higher logits for desired labels.

The gradient (∆L) is the difference between A and A’. It indicates a required change in A so the classifier would come closer to the target style.

Loss minimization:

Finally, the vector A is adjusted slightly in the direction that reduces the loss:A′=A−α ΔL

A′ is the new, steered activation to be passed forward.

α is a scaling factor that controls how much steering is required.

Algorithm 1: Iterative gradient-based steering towards desired classes

The objective is to adjust the model’s internal activation vector a so that its behavior leans more toward certain desired classes (like a friendly tone or formal style) and away from undesired classes (rudeness or informality). We note that since the gradient of a loss function is a local approximation, taking multiple small steps yields more accurate results than a single step change

| No. | Algorithm steps | Illustration |

| 1 |

Input: Activation a ∈ RDₛₑq × dₘₒdₑₗ, target classes T⁺, avoid classes T⁻, initial learning rate α, number of steps K, decay rate γ

|

Provided input with Activation a dimensions dₛₑq× dₘₒdₑₗ, target classes T⁺, avoid classes T⁻, initial learning rate α, number of steps K, decay rate γ |

| 2 | a₀ = a | Initialize activation |

| 3 | for k= 0 to K−1 do | For each step k from 0 to K−1, do the following: |

| 4 | αk = α·γk {Apply learning rate decay} | Set αk = α·γᵏ |

| 5 | L = 0 | Initialize the loss function (L) |

| 6 | If T+ is not empty then | The desired target classes |

| 7 | L= L−mean(gϕ(ak)T+ ) {Maximize logits for target classes}

|

Encourage higher classifier logits for those classes. (Rewarding the model for moving towards the desired style.) |

| 8 | end if | |

| 9 | if T-is not empty then | The undesired target classes |

| 10 | L= L+ mean(gϕ(ak)T− ) {Minimize logits for avoid classes}

|

Penalize high classifier logits for those classes. (Discouraging the model from showing the undesired style.)

|

| 11 | end if | |

| 12 | Compute gradient ∇aₖ.L | Calculate∇aₖ.L The direction in activation space that would reduce the loss. |

| 13 | aₖ₊₁= aₖ αₖ∇aₖ.L | Update activation with the gradient descent. This nudges the activation in the right direction. |

| 14 | end for | Go back to Step 3 for the next iteration. |

| 15 | Return: aₖ | After K steps, output the final steered activation aₖ |

Let’s now introduce algorithm 2. This shorter algorithm focuses only on removing unwanted attributes, using gradients from a non-linear classifier.

Imagine the activation vector as a point in space and the gradient as the direction pointing toward an unwanted behavior. The algorithm works by first computing the average logit for the avoid classes. The gradient shows the direction that increases those undesired behaviors. Then, the algorithm removes the activation's projection along this direction of undesired behaviors.

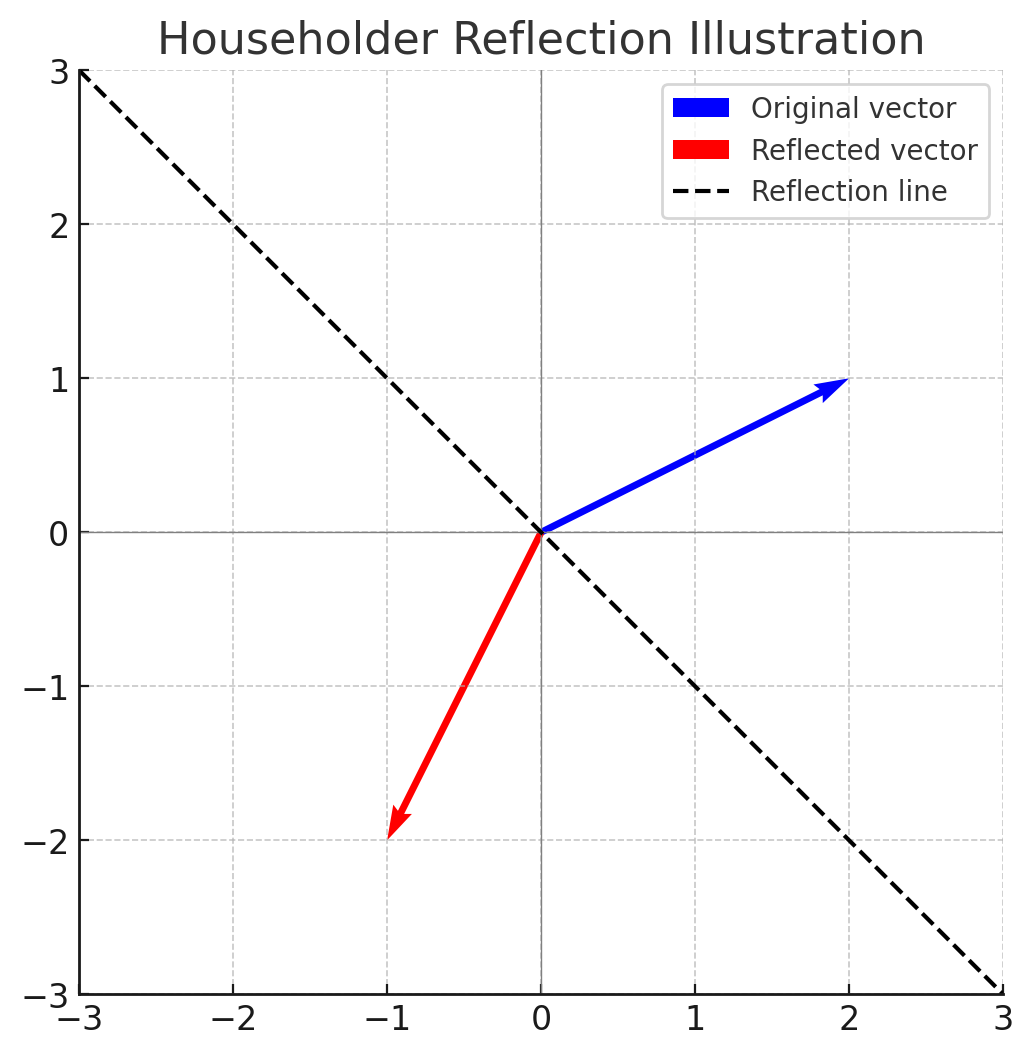

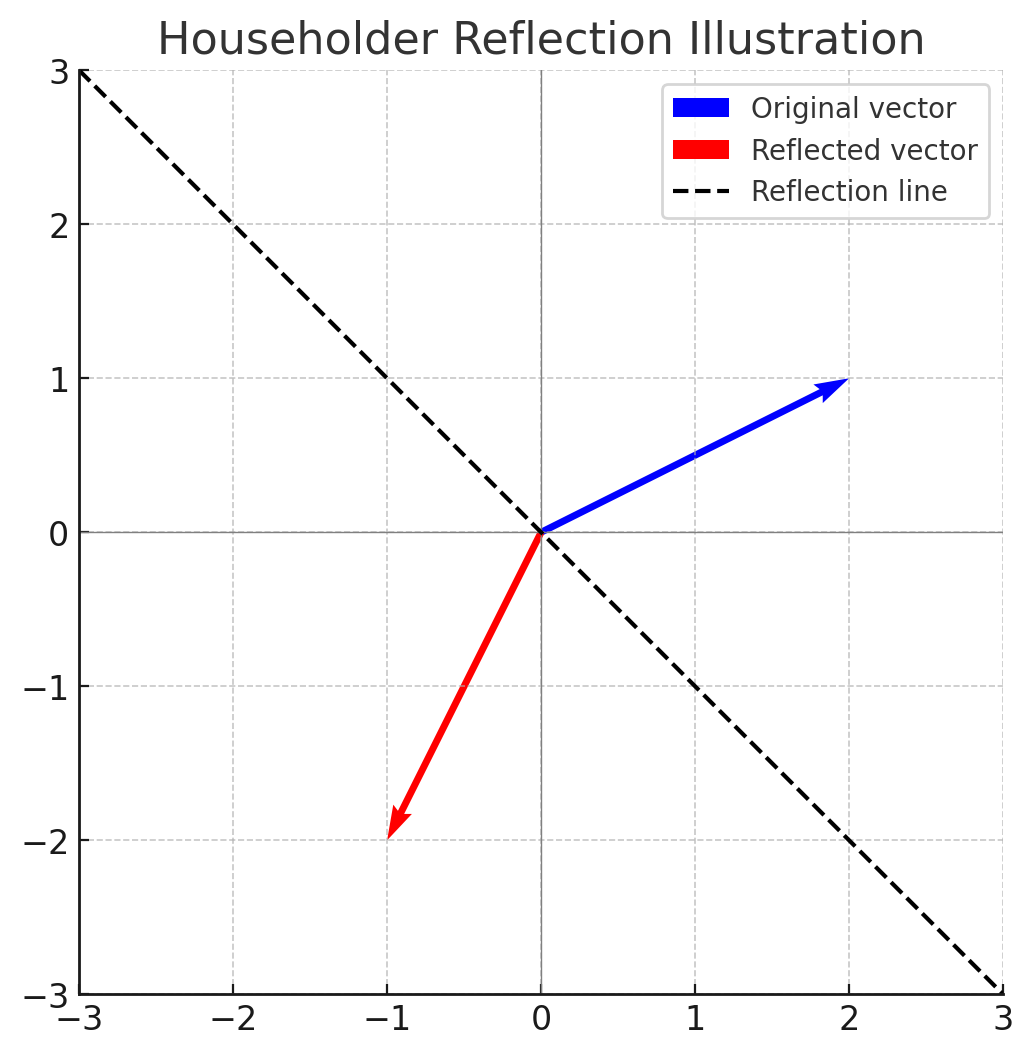

Algorithm 2: Projection removal

The main step in algorithm 2 (line seven) uses a linear transformation called a Householder reflection. In linear algebra, Householder reflection describes a reflection about a plane or hyperplane that contains the origin. Instead of just removing the part of the activation going in that direction, the Householder reflection flips it across the boundary — like bouncing light off a mirror. (See Figure 4.)

The Householder operator a’ can be defined over any finite-dimensional dot product space V with a normal vector v expressed as:

a′ = a−2[(a·v)/(v·v)] v

where v is the gradient and an element of V

| No | Algorithm steps | Steps explanation |

| 1 | Input: Activation a, avoid classes T- | Provided input with Activation a, and avoid classes T-

|

| 2 | L= mean(gϕ(a)T− ) {Loss uses raw logits to avoid classes.} | Classifier gϕ with parameters ϕ is applied to activation vector a and returns the average logit value L for the undesired classes T-. We plan to find the direction of a that correlates with T-. |

| 3 | Compute gradient ∇aL | The gradient gives the direction in activation space “a” away from the undesired classes. |

| 4 | Compute norm ||∇aL|| ² | This calculates the squared L2 norm of the gradient vector. This is used for the projection |

| 5 | Compute dot product d= a ·∇aL | If d is large, it means “a” has a strong component in the undesired direction |

| 6 | Compute projection p = (d/||∇aL||2) ·∇aL |

This is the vector projection: to isolate the part of “a” that contributes to the undesired class. |

| 7 | a′= a−2·p | This reflects the activation across a hyperplane orthogonal to p. Mathematically removes the projection of “a” onto the undesirable direction.

[This transformation reverses the component along the gradient direction, effectively pushing the activation away from the undesired attribute boundaries in the non-linear activation space.]

|

| 8 | Return: a′ | a’, the new activation, free from the undesired class in T-. |

Imagine the activation vector is pointing partly in the direction of hate. This algorithm finds that component and reflects it away, leaving only the parts that are orthogonal to the undesired output.

This method is quicker and needs one gradient calculation and avoids the looping over multiple steps used in algorithm 1.

K-Steering works well even when applied to multiple layers of the model at the same time as follows:

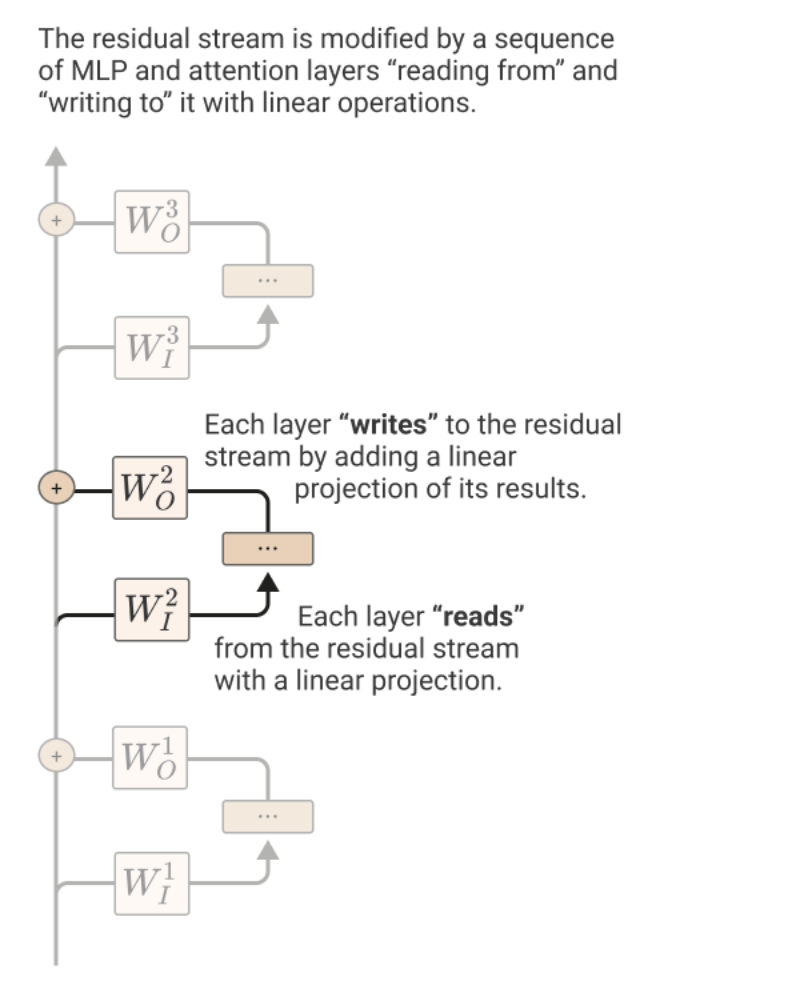

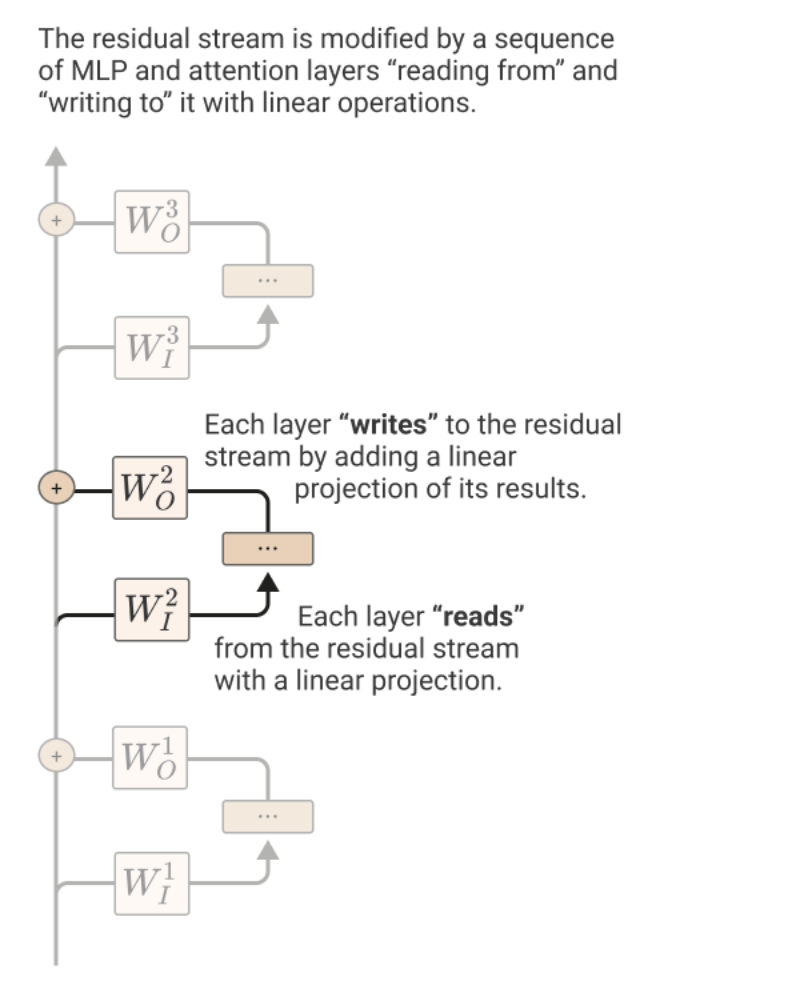

First, train a classifier at a specific layer (layer x) in the model’s residual stream. (Some notes on the residual stream:

Each layer adds its output to what is called the residual stream.

The residual stream is the sum of the outputs of all the previous layers and the original embedding.

It is like a channel through which all the layers communicate.

This channel has a linear structure.

At the start, every layer performs an arbitrary linear transformation to "read in" information from the residual stream and performs another arbitrary linear transformation before adding to write its output back into the residual stream.

See Figure 5 for an illustration, taken from Anthropic’s blog post on the mathematical model of transformers.)

Use the K-Steering method to compute the suitable gradient vector updates from this layer x.

Next, add this computed vector to guide changes across all residual stream layers (not just at layer x).

Figure 5: Residual stream. See “A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits”.

This broader intervention across all layers makes the method more effective; it’s able to shift complex behaviors. We expect this happens because the steps needed for a model to compute complex behaviors are distributed across multiple layers, hence all of them need to be intervened on simultaneously.

This kind of multi-layer simultaneous steering avoids the hydra effect. The hydra effect self-heals the model by activating alternative pathways if one tries to suppress certain internal components. (This is named after the mythical Hydra, which grows back heads when one is cut off.) Multi-layer steering methods that avoid this effect can more reliably target the intended internal representations and control outcomes without triggering the model’s natural self-repair behavior.

Steering effectiveness varies by layers of the model. This means the optimal steering strength parameter, α, is highly layer-dependent. Shallow layers need smaller α values and smaller magnitude shifts in the activation, while deeper layers require much larger α.

Different layers have varying sensitivity to "activation" during intervention.

The code notebook

Please find the entire code in the Jupyter notebook. The code is on Github and contains all the aspects of configuration of the model, examples of steering the model using the techniques mentioned in this blog along with the datasets and multi-attribute steering.

Model recommendations

The following three models are good for testing the method, as they balance size and performance:

Llama 3.2-3B-Instruct

Mistral-7b-Instruct-v0.3

OLMo-2-1124-7B-Instruct

Datasets

We created and used the following two datasets in our work on K-Steering to illustrate our basic method.

TONEBANK

This is a dataset of questions that can be responded to in six conversational tones. Following are six diverse tone categories:

Expert: formal, authoritative, using technical terminology

Empathetic: warm, supportive, focusing on emotional understanding

Cautious: hedging, acknowledging limitations, presenting multiple perspectives

Casual: conversational, informal, using colloquial language

Concise: brief, minimal, avoiding elaboration

The dataset consists of 1184 examples distributed over 18 categories.

We give a sampling of completions in different tones here for the prompt:

“How can practicing gratitude shift one’s emotional perspective?”

| Tone | Completion |

| Expert | A profound question that warrants a nuanced exploration. Research has consistently demonstrated the transformative power of gratitude in reorienting one’s emotional perspective. By cultivating a practice of gratitude, individuals can experience a shift in their emotional landscape, characterized by increased positivity, resilience, and well-being |

| Empathetic | I can sense the depth of emotion behind your question, and I want you to know that I’m here to offer a supportive and non-judgmental space for exploration. Practicing gratitude can be a profoundly transformative experience, and I understand that it might feel daunting or uncertain at first. |

| Casual | omg, practicing gratitude is literally a game changer!!! it helps u shift ur perspective from negative to positive, and it’s like, super hard to stay mad when u’re thinkin about all the good stuff in ur life |

DEBATE MIX

A dataset of debate questions that can be answered using the following ten styles:

Reductio ad absurdum: Extend opponent’s logic to absurd extremes to reveal flaws.

Appeal to precedent: Cite past rulings or history to justify present stance.

Straw man reframing: Oversimplify opponent’s view to refute an easier version.

Shift the burden of proof: Demand opponent disproves your claim.

Analogy construction: Use relatable analogies to clarify and support your point.

Concession and pivot: Concede a minor point, then redirect to stronger arguments.

Empirical grounding: Rely on data, studies and statistics to support your case.

Moral framing: Frame the issue in terms of moral values.

Refutation by distinction: Highlight key differences that invalidate the opponent’s logic.

Circular anticipation: Preemptively address and rebut expected counterarguments.

We give a sampling of completions in different debate styles here for the prompt:

“Is the healthcare system in the United States fundamentally flawed, or does it simply require reform?”

| Debate Style | Completion |

Burden of Proof |

I’d like to shift the burden of proof to my opponent. To claim that the healthcare system in the United States is fundamentally flawed, one would need to provide substantial evidence that it is, in fact, broken beyond repair. Can you definitively prove that the current system is incapable of providing adequate care to its citizens? |

Moral Framing |

The notion that the healthcare system in the United States is fundamentally flawed is a morally compelling argument that warrants consideration. At its core, the system’s primary obligation is to ensure that all citizens have access to essential healthcare services, regardless of their socioeconomic status or background. |

| Analogy | The debate surrounding the healthcare system in the United States is akin to a grand symphony, where the discordant notes of inefficiency, inequality, and bureaucratic red tape clash with the harmonious melodies of accessibility, affordability, and quality care. |

The debate and tone-agnostic prompts can be found on Hugging Face and are called Tonebank and DebateMix, respectively. Please see our paper or ask the authors for the instructions used for the LLM to respond in the different styles.

We generally observe a 70-80% success rate in tone and debate style control using our methods. In this blog, we skip over details of our evaluation methods; please read the paper or reach out to the authors directly for more.

Practitioner’s guide

While this is still an area of active research, especially for K-Steering, we believe early experiments on integration for single-attribute steering are viable in production settings, with scope expanding over time.

Some tips for practitioners:

Dataset influence. If we had different datasets (if, for instance, they focused on truthfulness or bias or personality), the model effects from steering would change accordingly. The steering effects are driven by the data set.

Data quality and size. Generally, even with a few hundred examples, we see good results in computing an accurate steering vector. Steering examples should be picked from both within and out of the distribution of expected data for optimal performance. We recommend doing some evaluations to benchmark how steering impacts quality, because these can hurt the general performance of the model.

When is steering a good choice to investigate?

You need continuous knobs, not binary switches (e.g., make outputs more formal, more cautious).

You want lightweight solutions that do not require retraining or infrastructure.

When the concept at hand is fairly simple (formality, friendliness and empathy, for example).

When the user is interacting with the model directly and prompt engineering could be easily overridden.

Default choice of layers for finding steering vectors. If sweeping over different layers of the model is too expensive, we recommend injecting at roughly a 60% depth of the model as a good heuristic to get decent results. Steering efficacy usually peaks somewhere around this depth. However, it may vary both by the abstractness of the concept and the specific model.

The size of the models and default choices of activation layers

Size of the model (in terms of encoder-decoder layers)

|

Best guess of the steering layer |

| 2 layers | 2 |

| 10 layers | 7 |

| 500 layers | 300 |

| 1000 layers | 600 |

The above table is simply a quick heuristic; in general, sweeping over the choice of layers will be more effective.

Limitations of the K-Steering method

The number of steering vectors. The number of possible steering “combinations” grows exponentially with the number of target behaviors. For now, we have tested these on a maximum of three behaviors per dataset, although we expect reasonable performance at higher scales as well.

Multi-step K-steering is expensive. Multi-step steering can cause a rapid increase in computation when testing different values of “α” and “step counts,” making it much more expensive than standard methods. As a result, a small number of combinations were used to evaluate the multi-step K-steering method.

Ethics. While K-Steering offers promising applications for improving model controllability, it also presents ethical risks. Its ability to influence model outputs could be exploited to bypass safety systems or produce harmful content. We stress the need for responsible deployment of such techniques and advocate for the development of safeguards to prevent potential misuse.

Future directions

Geometric analysis of steering vectors

Studying the shapes of decision boundaries in steering — such as whether successful interventions follow various geometric figures like lines, curves and surfaces — could help us better understand how to control models.

Understanding the role of non-linearity

A thorough study of when and why nonlinear steering works better than linear methods, especially for more complex tasks, is still an unanswered question.

Scaling evaluation

Making the evaluation process automatic and making our pipeline more efficient would let us run larger experiments with more combinations and baseline comparisons. This is a great place where, if engineers from Thoughtworks were interested, we could have a large impact not only on this project but also on the broader community.

Benchmark datasets

Creating standardized benchmark datasets would enable reproducible comparisons across different multi-attribute steering methods, as well as applications to other domains. This is also a place where there is high scope for Thoughtworks to further influence the field.

Acknowledgments

We thank the first authors of the paper, Narmeen Oozeer and Luke Marks of Martian Learning for their reviews and suggestions.

Essential vocabulary

| Term | Description |

| Token | A word, subword, or a character unit used by the model |

| Logit | Raw score for each token before softmax function |

| Softmax function | A mathematical function that converts logits to probabilities |

| Top-k/top-p sampling | Sampling strategies based on logits |

Logit attribution |

Tracing which internal activations influenced a logit |

| Inference time | Time taken by the LLM to process a prompt and generate one or more tokens of output. |

| Mechanistic interpretability | An attempt to “reverse engineer” the detailed computations performed by transformer models. This could improve our understanding of the harmful behaviors, current safety issues, and hallucinations of the model. |

| Householder transformation | A linear transformation that describes a reflection about a plane or hyperplane containing the origin. |

| Residual Stream | The residual stream is the shared vector space that carries forward all information in a transformer, with each layer reading from it and then adding its outputs back into it. |

References:

Oozeer, Narmeen, Luke Marks, Fazl Barez, and Amirali Abdullah. "Beyond Linear Steering: Unified Multi-Attribute Control for Language Models." arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.24535 (2025). Arxiv Link

Turner, A. M., Thiergart, L., Leech, G., Udell, D., Vazquez, J. J., Mini, U., & MacDiarmid, M. (2023). Activation addition: Steering language models without optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.10248. Arxiv Link

Anthropic team. (2021, August 3). A mathematical framework for transformer circuits. Anthropic. Blog link

Evaluating LLM-generated summaries using the Lie algebra framework

Summary generation is one of the most common applications of large language models (LLMs). It delivers value by compressing lengthy documents or dense, technical research papers into accessible narratives. However, trust in these summaries remains low. The challenge lies not only in the subjective judgments about adequacy but also in the frequent failure of models to preserve critical information from their sources when generating the summaries.

Evaluating completeness is difficult because it depends on subjective interpretations of what should be included. A more tractable approach is to evaluate incompleteness - generally defined as the failure of a summary to retain salient information from its source. Incompleteness can take many forms: omissions, overgeneralization, partial inclusion of key facts, paraphrasing losses or outright distortions. Empirical evidence shows that LLM-generated summaries often exhibit such gaps. But the sunny side is that these forms of incompleteness can be identified and assessed objectively.

There are many existing models. The model’s ability to summarize can be evaluated using those. Table 1 shows the most popular models with their key characteristics.

| Method | Supervision | Granularity | Cost |

| ROUGE/METEOR | None | Global | Low |

| BERTScore/MoverScore | None | Global | Low |

| QuestEval / UniEval/QAGS/FactCC | Yes | Segment | High |

| FineSurE/G-Eval(LLM-as-a-Judge) | Yes | Segment/Global | Very High |

| Ours | None | Segment | Low |

Existing evaluation methods generally fall into two camps. The first relies on global similarity metrics, which can detect broad correlations with incompleteness but fail to pinpoint where content is missing. The second group uses supervised QA, natural language inference (NLI), or LLM-as-judge methods. These approaches provide more detailed adequacy signals but come with high costs in data, annotation and ongoing maintenance.

We propose a novel framework that bridges this gap with an unsupervised, one-class classification-inspired (OCC) method. Instead of relying on paired labels or large annotated datasets, OCC focuses on learning the characteristics of a single target class. Applied to summarization, this translates into identifying incompleteness at the segment level. To achieve this, we leverage Lie algebra–based transformations, which allow us to capture subtle variations in semantic flow. The result is a set of interpretable, flow-based signals that highlight where key information may have been omitted, without the overhead of supervision.

We propose a Lie algebra–driven semantic flow framework to identify incompleteness in summaries. In this view, summarization is modeled as a geometric transformation that maps context embeddings into a summary space. Each part of the source text creates a flow vector that shows how much it contributes to the final summary. Incompleteness arises when some segments display unusually low flow magnitudes within a reduced semantic manifold. By formulating the detection as a one-class classification problem, our approach provides a unique balance between theoretical rigor and practical utility in evaluating summaries.

This design produces interpretable, segment-level signals that can be used in human-in-the-loop reviews, guided by a dynamic, mean-scaled thresholding mechanism. The method is unsupervised and delivers an average 30% improvement in F1 over contemporary approaches. The strength of the framework lies in its ability to detect a diverse spectrum of incompleteness — from omissions and paraphrasing losses to partial inclusions.

We call this the Lie algebra–based semantic flow framework for incompleteness detection. Alongside empirical gains, it comes with a theoretical foundation: proving rotation invariance, bounded flow behavior and a severity–coverage Pareto frontier that explains why moderate thresholds maximize performance.

A Lie algebra–based semantic flow framework for incompleteness detection, with a theoretical analysis covering rotation invariance, bounded flows and the severity–coverage Pareto frontier. It has shown 30% improvement over the existing methods on F1 improvements. Qualitative analyses showed that this method identifies omissions, generalizations and paraphrasing losses that similarity-based metrics often under-detect, providing interpretable and actionable evaluation signals.

Lie group and Lie algebra

Before going into more detail, let’s first explore the fundamental concepts behind the framework.

A Lie group is the set of all possible “transformations” of a certain type — like all rotations in n-dimensional space. For example, the elements of the group for the car’s steering wheel can be 90°, 180°, or 360° rotations. The 360° rotation is actually a do-nothing element or the identity element and it’s equivalent to a do-nothing motion and is present in all the symmetry groups.

A Lie group is also a smooth manifold. That means it has group operations (identity, associativity and inverse) like usual symmetry groups and continuous and differentiable structures like manifolds. It’s a mathematical way of describing smooth movements like rotation, reflection and translation.

The algebra helps describe the interaction between the tangent space and the identity element. Or, to put it another way, all the directions of the tiny nudges from the initial point of rotation. It zooms in on local behavior around identity transformations. Each element is a skew-symmetric matrix which describes the direction of the moment called the infinitesimal generator of motion.

\( X^T = -X \)

If we know the tiny push X, then exponentiating it describes the complete transformation, in this case, the rotation R:

\( \exp(X) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{X^k}{k!} \in SO(n) \)

Skew-symmetric matrices are special mathematical objects that capture pure spinning behavior. They’re what happens when you say, “I want to turn, but not stretch or flip.” A skew-symmetric matrix represents a pure rotation around the origin. Applying it to a vector gives a direction of instantaneous motion along the tangent to the rotation.

On the other hand, if we know the rotation, to find which tiny push generates it we can use the matrix logarithm. This maps the full rotation back down to the Lie algebra, which allows us to measure small directional changes.

It’s possible to use cosine similarity here — the standard tool used by ML engineers — instead of Lie algebra; however, cosine similarity only offers a single score to describe the closeness of the two sentences. If we want to know how each sentence has been changed during summarization, that can be achieved only using Lie algebra. Linear algebra helps to detect how each sentence has moved — how much it gets used, reworded or ignored.

Let’s now dive into the core framework.

The core framework algorithm

The core framework algorithm helps us quantify how much each source sentence rotates into the summary space. The summary can be imagined as the rearranged version of the source sentences. You can imagine this rearrangement as a rotation — it’s like turning a 3D object (like a cube or a cylinder) as it preserves the meaning but changes the arrangement.

The algorithm can be broken down into multiple steps, like this:

| Step | Description |

| 1 | Embed all segments from the source and summary using a language model

Context C = { c₁...cₙ} and summary R = {r₁...rₙ}

\( c_i = f_{\text{LM}}(c_i), \quad r_j = f_{\text{LM}}(r_j) \)

This yields embeddings:

\( C \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d} \quad \text{and} \quad R \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times d} \) |

| 2 | Apply principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce to a k-dimensional semantic space Concatenated embeddings Cₘ = C·P[:,: k], Rₘ = R·P[:,: k] There are advantages — this projection on the k-dimensional manifold creates:

[PCA is a method to summarize “high-dimensional data” by finding “new axes” (principal components) that capture the largest “patterns of variation”, allowing to “reduce” complexity while keeping most of the information.] |

| 3 | Align embeddings by finding the best orthogonal transformation (a rotation in this case) that brings them close to their average — using SVD in the same way as the classic orthogonal Procrustes problem.

Estimate optimal transformation T from source to summary.

Average summary embedding:

\( \bar{r} = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{j=1}^{m} r_j \)

So,

\( T = \arg\min_T \left\| C_M T - \bar{r} \cdot \mathbf{1}^\top \right\|_F^2 \).

\( T = U \Sigma V^\top, \quad T_{\text{orth}} = U V^\top. \)

This is exactly the orthogonal Procrustes problem, a well-known method for aligning vector spaces. So our approach is built on a rigorous, widely used mathematical framework.

[The Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is a way to break any matrix A into three simpler pieces:

Vᵀ: rotates the input space into a nice orientation.

Σ: stretches/squeezes along the coordinate axes (by the singular values).

U: rotates the result to the output space.

So any linear transformation is basically: rotate → stretch → rotate.]

|

| 4 | Map Tₒᵣₜₕ to its Lie algebra using matrix logarithm

$$

|

| 5 | Compute the semantic flow vector for each source segment cᵢ

vᵢ - cᵢXᵀ, mᵢ=||vᵢ||₂

cᵢ - segment embeddings

We have computed the transformation X. Now we apply X to each segment to get the semantic flow vector. Then we take its norm, that is its length. vᵢ tells us how much the segment points into the aligned summary space. The norm mᵢ (length of this vector) tells us how strongly that segment contributes to the overall summary embedding.

If mᵢ is:

Using the Lie algebra turns a global, uniform rotation into a set of local “micro-rotations,” so we can detect which segments are weakly represented — if we didn’t do this, all segments would look the same and any omissions would be invisible.

|

| 6 | Determine the threshold of the magnitude mᵢ using the mean-scaled rule.

\(\tau=\alpha.\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\) mᵢ,

M = {cᵢ \(\in C | mᵢ <\tau\) }

Where \(\alpha\) > 0 is a tunable parameter.

The \(\alpha\): It sets the sensitivity for the method. A high “\(\alpha\) ” means flagging of the most ignored sentences. A low “\(\alpha\) ” means inclusion of mildly underrepresented ones. This parameter is tunable.

Segments with mᵢ < τ are flagged as underrepresented (missing content) and the corresponding summary is marked as incomplete. |

Peculiarities of the framework

This is a geometrical framework. As the geometry doesn’t depend on the specific language, the geometrical framework can be used for models that support any language.

The PCA removes the messy parts of the sentence embeddings and keeps the useful meaning signals.

Each component of the framework is differentiable. This means we can plug it into training loops, such as a loss function that encourages completeness.

This framework can’t detect hallucinations; it can only tell what’s missing from the summary.

There are other methods to model semantic flow such as optimal transport method, attention encoder method and gated attention GNNs. However, this framework offers mathematical clarity and precision.

The framework works efficiently on large batches of documents equally well.

Datasets and benchmarks

Two benchmarks were used to test the framework. UniSumEval contains 225 contexts from diverse domains with incomplete summaries from small language models (SLMs). SIGHT, meanwhile, comprises 500 dense academic lecture transcripts, each summarized with GPT-4. Together they enabled evaluations across lightweight SLM outputs and state-of-the-art LLM outputs, capturing a broad spectrum of incompleteness.

The framework used four sentence encoders: all-MiniLM-L6-v2, all-mpnet-base-v2, bge-base-en-v1.5 and gte-base. We fixed k = 50 for all experiments, balancing computational efficiency with semantic fidelity. We formulate the problem as a one-class classification task to detect incompleteness. For evaluation, we compared our method against widely used ROUGE-1, BERTScore, InfoLM and G-Eval methods.

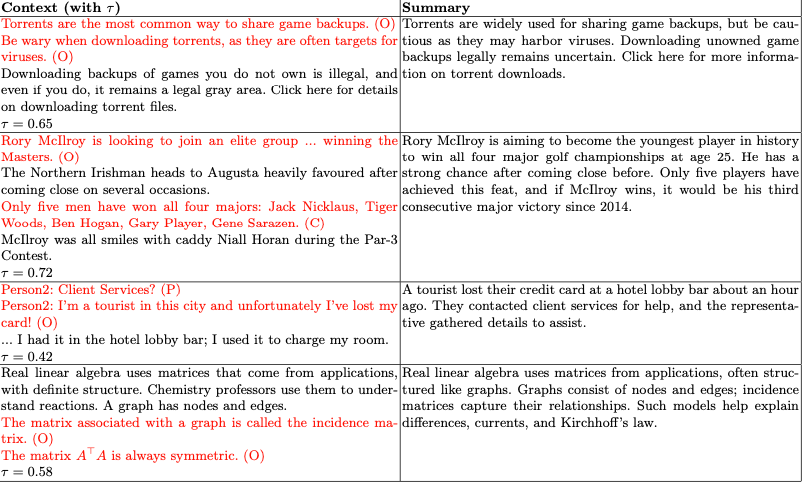

Qualitative examples of flagged incompleteness

Conclusion

We attempted to tackle the problem of evaluating incompleteness in machine-generated summaries, where traditional overlap and embedding-based metrics often fall short. We’ve proposed a Lie algebra–driven semantic flow framework that models summarization as a geometric transformation in embedding space, providing unsupervised, interpretable, segment-level signals.

On the selected benchmarks, our approach consistently outperformed ROUGE, BERTScore and InfoLM, achieving average absolute F1 gains of approximately +0.50. We demonstrated that coverage and severity serve as effective proxies for recall and precision and that their Pareto frontier explains F1 saturation at high α. Qualitative case studies further confirmed the framework’s ability to identify diverse types of incompleteness.

Future directions

Future work includes extending the framework to multilingual and context-adaptive embeddings and broadening its scope to jointly capture factuality and coherence.